Misplaced Confidence

“I've learned more about people through my association with aviation than I ever did about airplanes.”

~Paul Poberezny, Founder, Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA).

“Ditto.”

~Kerry Fores

I’ve experienced experimental aviation from many perspectives. Some are common: enthusiast, dreamer. Others are less common: scratch building an airplane to completion, performing the first flight, logging 500 hours in an airplane built in a garage. But becoming involved with an upstart kit plane company is an experience few are afforded and one I’ve been lucky to enjoy. My opportunity dawned in 1997 when airplane designer John Monnett disclosed to me a then-secret design called “Sonex.” I was enamored by the airplane and watched the prototypes evolve. In 1998 I carted home an incomplete set of plans, ordered thirteen large sheets of aluminum, and began building my own Sonex.

In 1998 there were few builders of this new airplane, the plans were still being developed, the “kit” was minimal, and the model-specifc knowledge base within the builder community was small. Those of us that were early adopters knew we may face challenges but we were committed to our projects by a belief in the design and a belief in our own abilities to push past any challenges we may encounter. And let’s be honest, building even the most popular airplane design is going to present some personal challenges.

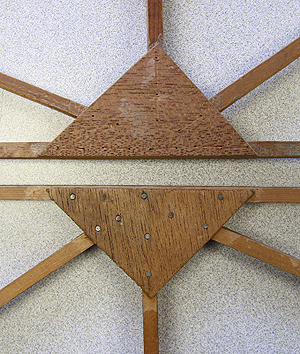

Here I share the finer points of making a formed aluminum rib with Sonex Aircraft workshop participants. Photo by Mark Schaible.

As I built my Sonex I also volunteered at Sonex Aircraft builder workshops and staffed the Sonex booth during AirVenture. I developed builder support documents in exchange for 10,000 rivets. In 2003, as the result of my carefully orchestrated begging, I was hired as Sonex Aircraft’s first non-family employee. A year later I fulfilled my decades-old dream when I completed and flew my homebuilt aircraft, Metal Illness. In the years that followed my position at Sonex Aircraft evolved and since 2007 my primary role has been Technical Support Manager. While serving in that position I’ve learned plenty about airplanes and engines, but I’ve learned more about people. Airplanes and engines are collections of parts with specific missions and predictable relationships to one another. People are collections of thoughts and emotions with predictable reactions to outside opinions.

Having experienced both the hobby and the industry of homebuilding, and having supported thousands of builders, I’ve learned the two most important ingredients for homebuilding success: money and time, rather….desire and passion. I’ve also learned a key way to fail; misplace your confidence.

Steel Your Confidence

Sonex Aircraft hosted builder workshops to acquaint both new and experienced aircraft builders with the tools, techniques, materials and plans-reading skills necessary to build an aluminum airplane. Participants spent a portion of their time building a wing leading edge project. The project was detailed in blueprints distributed to each participant. Before they began work I’d caution them not to copy their neighbor. An inexperienced builder carefully absorbing the plans may feel pressure if their neighbor is confidently cutting and bending aluminum. They may assume their neighbor knows what they are doing, abandon their careful approach to the project, and follow their neighbor’s lead. It’s human nature. The participants who appeared confident didn’t always know what they were doing but charged forward, bold in their ignorance. It wasn’t uncommon to see the same mistake repeated around a workbench, be it an assumed dimension, errant advice regarding a tool or technique, or a significant deviation from the plans. Errors could spread through the room like the flu through kindergarten. Even experienced builders encountering new (to them) materials and tasks can feel their confidence wane. It’s normal, as is assuming the person next to you knows what they are doing.

If you place your confidence in the hands of others—maybe from fear of asking what you think is a stupid question—and copy another builder’s methods or advice, you are at risk of making a significant error. I saw this happen when a builder shared with the Sonex builder community his “simplified” way to rig the wings. It was easier, but it was also wrong. The builders that followed his advice never questioned his approach, which differed significantly from the factory-defined method. I had to tell several builders that their wing spars needed significant rework. Those builders misplaced their confidence by believing the correct method was difficult.

Unlike copying, conversation brings ideas together for discussion. But this can have pitfalls as well. Some may get bogged down in indecision from too many opinions. This applies to tool selection, building techniques, interpretation of instructions, favored suppliers, etc. One builder may preach the use of a CNC machine to make parts, other builders will reveal it isn’t required. A particular builder may be a machinist with access to CNC equipment and the training to use it. Most of us are not machinists, nor do we need to be. The letters “CNC” conjure images of engineering degrees and expensive equipment, two things most homebuilders do not have, cannot afford and do not need. While some builders do use CNC machines, I proved an aluminum airplane could be scratch built without a band saw or drill press within 400 feet of your workspace. Don’t let one builder’s knowledge, tools, or perceived skill level steal your confidence. You must steel your confidence.

The All-Consuming Internet

“To fly, the Wright Brothers had to conquer the forces of lift, drag, thrust, and gravity. A fifth and far greater deterrent to flight had not yet been invented; the Internet talk group.”

~Kerry Fores

The Internet is a great place to go when you need to be paralyzed by fear or indecision. A new or perspective builder may spend hours absorbing advice dispensed in the talk groups and on builders’ websites. Not all contributors have the knowledge to back their advice and someone new to a design doesn’t have the knowledge to filter good advice from bad. It’s like panning for gold without knowing what gold looks like. My technical support role has provided me a unique window to builders; I see advice being disseminated on the Internet, by whom, and I have the technical support history of the people dispensing advice. Some builders type knowledgeably from their position of inexperience.

Building a gusseted wood rib can lead a new builder into a rabbit hole of opinions. How big should the gussets be? What shape? Should they be nailed? If nails are used, should thy be removed after the glue dries? Are staples better than nails? What kind of glue?

Before the Internet resided in the palm of everyone’s hand (or even existed), homebuilders supported each other with newsletters. People with a solid knowledge of a particular aircraft (often the designer or a widely acknowledged expert on the design) edited the newsletter and erroneous information never made the cut. The Internet has no editor. The Internet gives everyone a voice even if they lack skill, aptitude, knowledge, or ability. Someone that freelanced their way through an assembly may make it their mission to warn all builders of an “error” in the plans, the plans they did not follow.

“What do people have problems with?,” I’m often asked. My response is, “Everything.” But not everyone has a problem with everything. Many builders have no problems at all. Other builders populate my inbox on a daily basis. A perspective builder who believes they are performing due diligence by absorbing years of talk group archives will come to believe their chosen airplane is unbuildable, but that wouldn’t explain the hundreds or thousands that have been built. When you browse the archive of a talk group and sift through websites, question whether advice dispensed in 2001 is still applicable. Has the kit manufacturer updated their plans? Improved a part? Changed a material? Maybe the problem was of the builder’s own doing. Was the issue resolved when the builder contacted the factory but the builder never updated their blog? Be particularly wary of advice that mandates significant modifications are needed to parts or procedures.

After a builder chided me that “everyone” has the same problem they did, I searched the Internet with the random phrase “1996 Jeep door wiring.” The result was startling. My Jeep should have been suffering from chronic wiring problems at the door hinge, but––and this is important––it wasn’t. Never even a hiccup. I could have shared my positive experience with the Jeep groups but most people don’t do that, do they? The people experiencing a problem post, often several times, skewing the results, and the people who had the problem respond with myriad remedies and preventative measures. No one shares when things go well. “My backup lights worked today. That’s 21 years in a row.”

Neighbors with Initials

“The EAA Tech Counselor, the FAA inspector, and two A &P's say I've got everything right. Here's what I want you to do: Talk to the experts I've assembled for you.”

~Identity withheld

I received the above email from a builder with whom we had reached an impasse. His “experts” were backing—or feeding—his issue and we could not get him to listen to our advice. Unknowingly, he identified other thieves of confidence: hangar mates, EAA Chapter members, the FAA, and aircraft and powerplant (A&P) mechanics. Did you just gasp? I’ll explain. Inexperienced builders are at risk of being led astray by their naivety and are susceptible to believe the “experts” know more than they do. They don’t. At least not by default, title, or club affiliation. Your hangar mate may be a whiz with Polyfiber and clueless with fiberglass. Your DAR or FAA inspector can be thoroughly familiar with Continental engines, but your Jabiru 3300 may be the first one they’ve seen. When people sporting initials (A&P, AI, DAR, FAA) make demands, we mortals question if we have any business building an airplane. I assure you, we do.

My garage-built Sonex, "Metal Illness," sharing a hangar with a T-6 Texan and a DC-3. An aircraft a powerplant mechanic may be a whiz with the radial engines on these classic aircraft but completely unfamiliar with the Jabiru engine in my Sonex.

This is not an attack on any group’s knowledge or experience; it is a caution that their knowledge and experience may not translate to your project. Nor does it need to. Although Experimental Category aircraft do not have to adhere to the strict requirements defined by the FAA for Standard Category aircraft, that does not make experimental aircraft less safe, it makes them available and potentially innovative. Some Sonex builders have asked if they can substitute solid rivets or, as they often say, “real” aircraft rivets for the stainless steel blind (“pop”) rivets used to construct a Sonex. When I tell them the blind rivets are twice the strength of the “real” aircraft rivets they want to use, most of them change their mind. Conversely, builders of other aircraft designs should not assume they gain strength by substituting solid rivets with blind rivets. Rely on the designer’s choice of hardware, not the casual suggestion of someone who does not know the engineering behind the design

Build it as it was Designed

“With a few modifications, you can build a nice Pietenpol. With no modifications, you can build a great one.”

~Unknown

That quote applies to any successful design. I say “successful” because the history of homebuilding is strewn with poor designs and builder communities left caring for orphans. If you’ve chosen a successful design from a reputable company you will do well to build it the way it was designed. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t add your own personal touches—that is part of the joy and spirit of homebuilding—but installing an engine that exceeds the design’s limits is not the way to express yourself. The longer you lurk in an Internet talk group the more recommended changes you will be exposed to. Even the smallest change can ripple through a project, leaving you facing unforeseen complications and a significant increase in build time. Here is some good advice borrowed from a friend (thanks, Tony) who is building his fifth homebuilt, “Build it the way it was designed and after you’ve been flying it for a while you will know what, if any, changes you want to make.”

The kit designer should be your first stop for technical support. No one knows the product better or has more interest in your success.

On a similar note, I’ve found it’s fashionable for some to hold forth that “the factory” doesn’t know what they are doing. When you see such claims, question the source and their motivation. Do they have a competing product to sell? Have they caused their own problem by not following the plans? No well-intentioned kit plane manufacturer benefits from misleading their customers or shipping inferior product. A company’s success depends on their customers’ success. Deceit may sell twenty airframes but the truth will sell 500. Successful customers will sell another 500. Having built and flown the products I support, it’s always fun for me to read something can’t be done.

Sonex serial number 1, photographed in May 2017, still wears its experimental cowl configuration from 1998. The cowl cut-outs of this prototype Sonex differ from what is shown in the plans, causing some customers to argue they were sent the wrong cowl or the wrong plans.

Ironically, “the factory” can lead builders astray. The Sonex Aircraft factory fleet has been scrutinized at nearly seventy builder workshops and over forty major airshows. Builder’ brought their very pointed questions (“Can I sleep in the back of the fuselage?”) and their digital cameras. They combed over every detail, took close-up photos, and tapped oil-stained fingers on a control surface while contemplating its construction. They’d tug me over and ask why we have a clevis pin where their plans show a bolt. I’d explain that the airframes they were scrutinizing were prototypes and none had been built from the plans. The factory airplanes were built from engineering studies, napkin sketches, and trial and error. It was while building the prototypes that the specific details were developed and incorporated in the plans. Be careful, please, comparing the photos you’ve harvested at factories and fly-ins to your plans and kit parts.

Have Your Own Experience

If I told you I had a flat tire driving through Denver would you avoid Denver in fear of a flat tire? No, of course not. Hundreds of things could go wrong driving through Denver yet the overwhelming majority of people get through without incident. Don’t anticipate problems. Countless builders have emailed me after completing a task they feared for weeks (or years) to tell me how well it went. Their fear was conceived and nurtured by other builders.

Don’t misplace your confidence. If the desire to build an airplane burns within you, and you’ve identified the design that fits your mission, you have what you need to be successful. If you are in the midst of a project and feel overwhelmed by decisions and advice, turn off the computer, put aside the smart phone, and lock your shop door. Have your own experience.

A version of this article appeared in the November 2017 issue of KITPLANES Magazine.